San Diego County’s first African-American homesteader and a local legend, Nathan “Nate” Harrison was born a slave in Kentucky in circa 1833. He was brought to Northern California during the Gold Rush, migrated southward through the state as a rancher, timber man, and laborer, and settled in San Diego County in the 1870s. Harrison was an integral part of the ethnically diverse rural community in and around Southern California’s Palomar Mountain for nearly half a century before passing away in 1920.

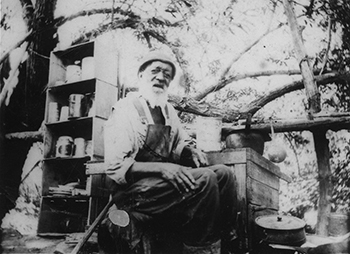

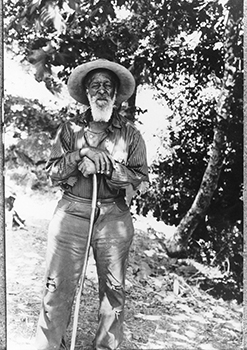

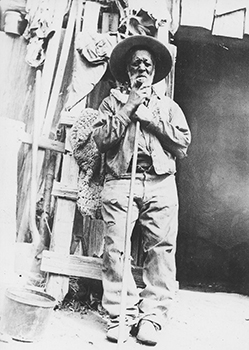

Harrison’s remarkable longevity—especially for someone who endured slavery, the Gold Rush, and the Wild West—was matched only by the iconic status he achieved during his lifetime and in the decades to follow. The many tall tales, myths, and legends of Harrison made him the Forrest Gump of Old San Diego; he was allegedly present at every prominent moment in the region’s history. Furthermore, Harrison was San Diego’s most-photographed 19th-century resident and played a prominent role in the region’s first tourist destination.

The child of Ben and Harriet Harrison, Nathan “Nate” Harrison was born into slavery in Kentucky in the 1830s. Virtually nothing is known of his childhood. As a young man, he traveled west with his owner, Mr. Harrison, during the early years of the Gold Rush (1848-52). Nathan Harrison worked as a miner in Northern California’s mother-lode region in the 1850s and early ’60s.

Following the death of his owner, Harrison migrated southward toward Mission San Gabriel in the 1860s, working as a rancher, timber man, and laborer. In the 1870s, he frequented many parts of San Diego County, including Pauma Valley and other northern inland areas, as well as the city of San Diego; Harrison found regular work all over the region as a rancher, timber man, laborer, cook, and shopkeeper.

It was during this time that Harrison married an indigenous woman with children from a previous union; their marriage was brief, although he would remain close to her family.

In 1882, Harrison sold his property to Andreas Scott and left Rincon, although he stayed in the general area and worked at Warner’s Ranch and in Temecula for a few years. Harrison married again in the late 1870s or early ’80s, this time to an Indian woman named Dona Lavierla; they were not together long.

In the late 1880s, Harrison made his home two-thirds of the way up the west side of Palomar Mountain; he claimed the tract’s water in 1892 and homesteaded the land in 1893. Harrison lived on Palomar Mountain from at least the late 1880s through 1919.

During his early years on the mountain, Harrison was busy in many local industries, including shepherding, cattle tending, bee keeping, and horticulture.

In his later years on Palomar—especially after the County widened his road and made it a public highway in 1897—he became a popular attraction for tourists, visitors, and friends, who helped to sustain him with regular gifts of food and other supplies.

During a visit by acquaintances in October of 1919, an ailing Harrison was convinced to leave the mountain and receive medical attention.

Now in his eighties, he lived for an additional year in the San Diego County Hospital before dying there on October 10, 1920. Harrison’s body was immediately interred in an unmarked grave in Mount Hope, the city cemetery.

A mere sampling of historical narratives includes the following list of conspicuous yet dubious claims in chronological order:

An undeniable part of Harrison’s legacy is the numerous photographs taken of him by visitors to his Palomar property. We have compiled over 30 different images, but it is likely that more exist. This is a remarkable feat considering he lived so far from the urban center of the city in which most of the region’s cameras were located. Harrison was photographed far more than any other local legend who lived in San Diego, including famed Kansas lawman Wyatt Earp (1848-1929) who arrived in booming San Diego in the 1880s, celebrated American booster Alonzo Horton (1813-1909) who laid claim to the title of father of the city of San Diego, and many others. Somehow, this non-wealthy, non-white, non-San Diegan became the region’s first photographic sensation.

The factors that contributed to Harrison’s prominent presence in front of a camera were intertwined with key aspects of his identity, community, and the overall mountain landscape in which he lived. The pictures were powerful symbols. Furthermore, the photographic process was rife with symbolic behavior. Appreciating the context, meanings, and ramifications of both process and product were essential to gaining a greater understanding of Harrison’s life and legend.

{Click on an image below to enlarge}

Nathan Harrison interacted with thousands of people during his life, but there were only a few dozen who were referenced repeatedly in the historical records. Many of these individuals cultivated an extended connection with Harrison, appearing and re-appearing as part of his community of family, friends, co-workers, employers, benefactors, etc. In alphabetical order, they included:

Amy (no last name recorded), also known as “Cubby”: The African-American servant of Irene Doane and a friend of Harrison, Amy only worked for the Doanes for a short period of time (1904-05) before returning to her Louisiana home.

Robert Asher: A close friend of Harrison and long-time resident of Palomar Mountain, Asher penned multiple accounts of the region’s nineteenth-century events and occupants A Palomar Mountain resident for over three and a half decades, Robert Haley Asher was an expert on local history, horticulture, and geology. He was also an accomplished photographer and painter who captured much of the local history on paper, film, and canvas. Born in 1868, Asher homesteaded Palomar Mountain land that he ultimately donated to the Baptist Church in 1933. This land would eventually host today’s Palomar Christian Conference Center.

Adalind Bailey: Longtime Palomar Mountain resident Adalind Bailey was the wife of Milton Bailey and the daughter-in-law of local pioneer Theodore Bailey.

Hodgie Bailey: The youngest daughter of Theodore Bailey, Hodgie married local rancher Louis Salmons; she became an accomplished oil painter whose work was in high demand across Southern California.

Milton Bailey: The son of Theodore Bailey, Milton created a stage line between San Diego and the Bailey resort (Palomar Lodge) in 1912 that brought many visitors to Harrison’s cabin.

Theodore Bailey: Hailed as “the sage of Palomar,” Theodore was the Bailey family patriarch and one of Harrison’s biggest champions; Theo Bailey was so overcome with emotion at Harrison’s mountain memorial service that Ed Davis had to finish the spoken tribute. Theodore Bailey, like his dear friend Nathan Harrison, was born in Kentucky. Theo lived in Kentucky and Illinois before trekking to California. He moved from Long Beach to Mesa Grande in 1884 and finally to Palomar Mountain in 1887. The Bailey family built a home on the east side of Palomar Mountain. The house would be a focal point of activity for the mountain community for over 70 years. Theo died in 1926.

William Boucher: A Palomar homesteader, Boucher (pronounced Boo-ker) was a Harrison neighbor and friend; he helped build the mountain’s west grade that bore Harrison’s name.

Encarnacion Calac: The wife of Rincon Chief Juan Sotelo Calac, Encarnacion was Harrison’s godmother; the two were close friends and often spent entire afternoons in conversation and laughter.

Juan Sotelo Calac: A Rincon Chief, he baptized Harrison and gave him the confirmation name “Inez.” The Calacs were descendants of Manuel Olegario Calac, the Luiseño leader that actively resisted unlawful indigenous evictions at the hands of the U.S. government. He was a key figure in pressuring the American federal government to create multiple Southern California reservations.

Dory Mary Carricaburu (neé Smith): Harrison’s step-granddaughter, Dory Mary was Fred “Sheep” Smith’s daughter.

Embedded photo here: Figure 19: This photograph of Dory Mary Smith’s step-granddaughter was found decades ago in the Harrison cabin.

Herbert Crouch: A friend and business partner of Agua Tibia Ranch’s Major Lee Utt, Crouch likely employed Harrison to tend to his extensive sheep holdings.

Edward Davis: A close friend of Harrison, Davis wrote multiple histories of Palomar Mountain and took numerous photographs of the region. Travelling aboard a steam ship through the Panama Canal, Davis came to California from New York City in 1884. Ed Davis and his wife, Anna May, settled at Mesa Grande on a 320-acre ranch three years later.

Richard and Lois Day: Owners of the Harrison property for over three decades in the middle of the twentieth century, the Days compiled many written accounts and photographs of Harrison.

Ed Diaz: A local historian and community activist, Diaz was the person primarily responsible for locating Harrison’s unmarked Mount Hope grave in the early 1970s and raising the funds to obtain and place a permanent marker at the site.

George Doane: Unmistakable because of his waist-long beard, Doane was a memorable Palomar Mountain character and a close friend of Harrison. Born March 30, 1851 in Santa Clara County, California, George Doane clerked in the city of San Diego’s Alonzo Horton House hotel office before venturing to Palomar Mountain. Palomar pioneer George Dyche first encountered Doane in 1881 on the banks of the San Luis Rey River; Doane had few possessions besides the clothes on his back and a horse. Dyche took Doane in, fed him, and gave him a place to sleep for the night. The trek up the mountain was through the pouring rain, and (George Dyche’s son) Will distinctly recalled Doane wringing out his waist-length whiskers “like a wet garment in a wash tub.” This was Doane’s introduction to Palomar Mountain, a land that would become his home for 25 years.

Irene Worth Doane (neé Hayes): The teenage girl who answered George Doane’s advertisement for a bride, Irene was a Louisiana native who first came to Palomar Mountain in 1904.

George Dyche: A Rincon local who acquired Joseph Smith’s house, livestock, and other holdings in 1869, Dyche was a successful Palomar rancher who married a woman of indigenous descent and maintained close relations with the native population until his death in 1906. Dyche was a native of Berkeley Springs, Virginia (in today’s West Virginia); he crossed the country via wagon train as a teenager during the Gold Rush. After clerking in Sacramento and a successful stint in the Northern California cattle business, Dyche moved to Rincon, where he built a cabin and lived for many years. He married a Cahuilla Indian woman, and they had three children. Their oldest child, Will (born in 1869), was a close friend of Ed Davis and an informant for many of his Palomar Mountain histories. Will and his siblings were raised in the original Joseph Smith house.

Bentley Elmore: In charge of the county road that bore Harrison’s name and wound up the west side of Palomar Mountain, Elmore was also a friend to Harrison.

W. C. Fink: Having moved to Palomar Mountain in 1890s from Pennsylvania in the hope of curing the tuberculosis that had turned his voice to a perpetual whisper, Winbert “Little Fink” surprisingly outlived many of the local pioneers, including his acquaintance, Nathan Harrison. Fink saw the success George Doane had had in procuring a wife through a matrimonial agency and followed suit. Fink’s marriage, like Doane’s, was very short-lived.

Chris Forbes: A sheepherder for Harrison’s neighbors, Forbes was born in the late 1880s and had many childhood memories of his friend, Harrison, as an old man.

Nathan Hargrave: Derided and ostracized for being overly opportunistic by Palomar pioneers, Hargrave angered locals by surreptitiously acquiring Harrison’s mountain property at auction in 1913.

Edgar Hastings: A friend of Harrison, Hastings conducted many interviews with other Palomar old-timers in an effort to record the region’s history.

Robert Dewey Kelly: A member of the San Diego County pioneer Kelly family, Dewey owned and lived at the Harrison property from 1956-69.

Dona Lavierla: Harrison’s second recorded wife, Dona Lavierla was a Santa Barbara native of indigenous and African descent.

Frank Machado: Machado had a dual connection to Harrison; he was a neighbor of the Smith family into which Nathan Harrison first married, and later, Machado’s aunt, Dona Lavierla, wedded Harrison. Machado was a California Indian who owned land near the Lake Henshaw Dam.

James McCoy: The San Diego sheriff as well as a highly successful and well-connected land speculator, McCoy employed many laborers across the county in the late 1800s, including Harrison.

Enos Mendenhall: A North Carolina Quaker who came to California in 1849, Mendenhall was highly successful in acquiring land in and around Palomar Mountain and building the lucrative Mendenhall Cattle Company. Mendenhall—a former schoolmaster—worked in law enforcement when he first came to California, serving on governmental Secret Service vigilante committees in San Francisco before venturing to San Diego and up Palomar Mountain on official business to stop rampant cattle and horse thievery in the area. Enos did his best to rid Palomar of rustlers and then proceeded to start the most lucrative cattle business in the region. The Mendenhalls brought great fame to Palomar Mountain for their cattle business, which grew to include over 11,000 acres in the immediate area. Enos T. Mendenhall became so wealthy that during the 1880’s economic depression he gave gold money from his safety vault to Escondido’s bank in order to prevent a run on the bank.

Juan Murrieta: A prominent sheep rancher whose land became the city of Murrieta, Juan likely employed Nathan Harrison in the care of livestock. A native of Spain and born in 1844, Murrieta would own immense herds of sheep in Southern California. When he left the animal husbandry business in the late 1880s, he moved to Los Angeles and became the county’s first deputy sheriff.

Jean and Augusti Nicholas: Known commonly as “The Frenchmen” because of their country of origin, brothers Jean and Augusti Nicholas were Harrison’s neighbors, friends, and fellow shepherds.

Matthew Ormsby: A Bonsall pioneer who led his family from Arkansas to California via covered wagon after the Civil War, Matthew Ormsby, according to an unlikely story by his granddaughter, Bessie Ormsby Helsel, purportedly brought Harrison out west in 1868.

Ed Quinlan: A railroad engineer and frequent visitor to Palomar Mountain, Quinlan convinced a severely infirmed Harrison to seek medical treatment and leave his hillside home in 1919.

Max Peters Rodriguezés: Born in 1887 in a Pauma adobe house, Rodriguezés grew up in the general Palomar Mountain area at Pauma Valley and befriended Harrison; his grandmother was Harrison’s godmother.

Louis Rose: A renowned community advocate and developer, Rose was San Diego’s first Jewish settler and a friend and employer of Harrison.

Louis Salmons: Rancher Louis Salmons was another close acquaintance of Harrison who spent most of his life in and around Palomar Mountain; he married Theodore Bailey’s youngest daughter, Hodgie. Born in 1876 in Atlanta, Georgia, Salmons spent much time on Palomar Mountain with Harrison as a neighbor. Salmons would eventually settle on nearby Dyche Valley.

Frederick “Sheep” Smith: A prominent Los Angeles sheep rancher, Smith would become Harrison’s son-in-law when his mother married Harrison in the late 1860s or early ’70s.

Frederick Smith’s mother: An Indian woman from the Lake Elsinore area, Frederick Smith’s mother was Harrison’s wife; her given name seems to have escaped the annals of history.

Joseph Smith: Often credited as the area’s “first white settler,” Smith built his adobe-brick and hewn-timber house atop Palomar Mountain in the 1850s; a drifter murdered him in 1868, and Harrison was a member of the posse that avenged his death. A South Carolina native and former sea captain, Joseph Smith came to San Diego in the 1850s and accrued significant wealth by partnering in the cattle and sheep business with local entrepreneur E. W. Morse. In one of the crueler graveyard ironies, Smith and his killer were interred adjacent to one another at the site where the latter was executed.

Philip Sparkman: An expert on California Indian languages who lived at Pala and worked at the Rincon store, Sparkman was the Harrison friend who fronted his property taxes during the late 1890s and early 1900s. At the time of his death in 1907, Sparkman was noted as a native of England that was in his 50s with no relatives in the U.S.

Major Lee Utt: The founder of the Agua Tibia Ranch, Major Utt was often Harrison’s employer as well as a long-time friend.

Lysander Utt: A Tustin businessman with no verifiable connection to Harrison, Lysander Utt would dubiously be credited in the 1950s with having brought Harrison to California; he is often confused with Major Lee Utt.

William Veal: A San Diego deputy and developer, Veal purchased Pala Mission lands in the 1890s and married Dona Lavierla, Harrison’s second wife, soon after she and Harrison had parted.

John and Mary Jane Welty: San Diego County pioneers who migrated to the region from Missouri by covered wagon, John and Mary Jane Welty, according to a suspect account by their granddaughter Elsie Crook, brought Harrison to California.

Copyright © 2023 - All Rights Reserved | Document Reader